By Amanda Mattison

Imagine life in the Midwest during the Dust Bowl:

On those days when the wind stops blowing across the face of the southern plains, the land falls into a silence that scares people…because the land is too much, too empty, claustrophobic in its immensity…because people feel lost, with nothing to cling to, disoriented. Not a tree, anywhere. Not a slice of shade. – Timothy Egan, The Worst Hard TimeNow imagine this:

Lush, fertile fields bursting with golden grains, wide-open plains dotted with rich green plants, a vast cerulean sky dappled with rain clouds, a bare-backed farmer stepping his shovel into the rich loamy soil, and a woman in a knit cap clutching a prized chicken to her chest.Feel better? That’s American Regionalism.

During the 1930s and 40s, Americans were reeling from the Dust Bowl, the Stock Market Crash, and the Great Depression. The nation needed a lift. Several artists of the era sought to rekindle a sense of hope and pride in the American heartland, celebrating the resilience of both the people and their surroundings. A new movement was bourgeoning—a movement called American Regionalism.

The Rise and Fall of American Regionalism

American Regionalism is part of the greater American Scene Painting movement but was focused on the Mid-West and South. There is some overlap between American Regionalism and Social Realism, as many artists of the time were seeking to convey the deteriorating conditions of the working class, the experiences of marginalized groups, and governmental and social responsibility. Most American Regionalists, however, were traditional and conservative in style, focusing on scenes of life on the land, family life in small-town America, and a return to the nation’s agricultural roots.

Regardless of individual undertones, the movement was a collective rejection of the dominant European modernism and provided a way for artists to develop a distinct American style. Local, state, and federal agencies funded projects that included murals, illustrations, paintings, and lithographs.

American Regionalism, however, was short-lived, as the 1940s brought a transition to Abstract Expressionism. The movement also lost traction as authoritarian regimes in Europe began to use figurative and realist art as propaganda. Paired with the rumblings of impending involvement in World War II, this alarmed many Americans, and the American Regionalist movement subsequently developed a reputation as being retrogressive and overly nationalistic.

The Regionalist Triumvirate

Three artists who most exemplify American Regionalism are referred to as the Regionalist Triumvirate: Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Steuart Curry.

Grant Wood (1891-1942)

Grant Wood’s American Gothic not only stands as the epitome of American Regionalism; it is also among the most recognizable pieces of Americana. The piece, painted in oil on board in 1930 and housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, depicts what most Americans see as a farmer and his wife standing before their home. However, as Wood put it, “the prim lady with him is his grown-up daughter.” The female model for the image was Wood’s sister, and the male, his dentist. The “gothic” in the painting’s title refers to the gothic-style window of the house. Although there is much debate as to Wood’s intended message, he said, “These are types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life.”

Another of Grant Wood’s Regionalist pieces is Appraisal (1932, oil on board). The piece tells a tale of two different lifestyles (urban and rural) and brings attention to the importance of family farming at a time when poultry factories were becoming increasingly popular. Appraisal embodies one of Wood’s signature themes: the effects of modernism on provincial life.

Wood spent his childhood in Iowa and ultimately, after studying in Cedar Rapids and in Paris, returned to Iowa, as he put it, “to paint what I know” and “paint life as it is.” His paintings range from stylized renderings of pastoral scenes to portraits of demure or reticent family members.

According to the documentary film “Grant Wood’s America,” throughout his work, Wood aimed to capture a universal American character—a character he said he had been missing while trying to see America through the eyes of the French. He conveyed a confidence and pride in the heartland and celebrated the virtues and self-reliance of the frontier.

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975)

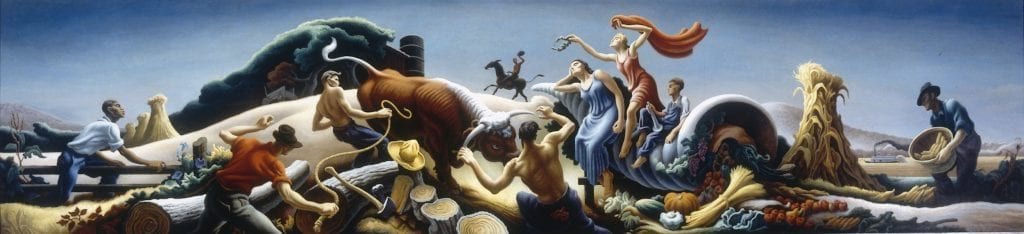

Achelous and Hercules, an egg tempera and oil mural (see below), was painted for a Kansas City, Missouri, department store in 1947 and is now held at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In the mural, Benton has intricately linked the midwestern harvest with the Greco-Roman mythology and origin of the cornucopia. Among a rich and varied scene, the piece includes a Herculean cowboy grabbing a bull by its horns; timber, vegetables, and sheaves of wheat; and a steamboat traveling along a river in the background.

After returning from his studies in France, Benton began traveling and painting scenes across America. His work includes paintings of pioneers, trappers, Native Americans, tobacco pickers, coal miners, and cowboys. He also became famous in Kansas City for painting murals of the everyday lives of Americans. Benton even spent time in the Navy drawing and painting ships for the military. He was the first artist to be on the cover of Time Magazine. He illustrated many books including Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, andGrapes of Wrath.

Benton was a colorful and rowdy character who tended to make waves on both the political and social front with artists and the general public. However, he maintained his reputation as a skilled muralist, painting until his passing in 1975.

John Steuart Curry (1897-1946)

John Steuart Curry is best known for his painting Baptism in Kansas (below, right). Painted in 1928 and first exhibited at the Corcoran in Washington, DC, the piece is now held by the Whitney Museum of American Art. In the scene, the preacher baptizes a woman in a water tank because the creeks have gone dry. This is an example of the American Regionalist message that people are generally resilient and that life continues even in the face of adversity.

Curry also studied in Paris and returned to America to paint realist scenes including the Oklahoma Land Rush. He travelled within the U.S. and at one point followed Ringling Brothers Circus. During that time, he painted plenty of circus images, but of behind-the-scenes depictions rather than performances. Along with his cohorts, he painted America in a way that was noble but not overly glorified.

Other American Regionalists

The Regionalist Triumvirate provides a glimpse into the ideals of the American Regionalist movement; however, there is much more to be explored. Other American Regionalists to investigate include John Rogers Cox, Marsden Hartley, Alexandre Hogue, Mattie Lietz, Margot Peet, and Edna Reindel. And artists like Andrew Wyeth and Norman Rockwell came in at the tail end of the movement – carrying American art from regionalism toward new directions. Some believe that the American Regionalist perspective continues to be uniquely interpreted today by American realists such as Bo Bartlett and Rose Frantzen. Time, as always, will be the judge.