By Mike Strickland

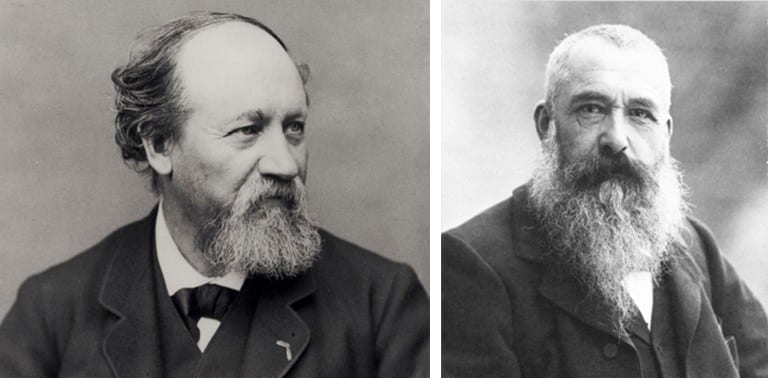

Perhaps nothing makes a teacher prouder than to have their students succeed. Almost everyone knows the name Claude Monet, but not as many know of Eugène Boudin, Monet’s mentor and friend. Claude Monet said of Boudin, “If I have become a painter, it is entirely due to Eugène Boudin.”

Eugène Louis Boudin was born on the northern coast of France in Honfleur on July 12, 1824. His father was a harbor pilot, so Eugène grew up around the ocean and ships, and this fueled his career as a marine painter. He studied painting briefly in Paris and began to paint the sea by 1853, preferring to paint outdoors where he could see and experience the light and colors of the sky and ocean. This practice made him one of the first plein air painters in France. Since Boudin painted mostly out of doors, many of his paintings are relatively small for portability. All of his paintings are amazing for their light and color. Boudin was known for his beautiful depictions of skies and water, and for his accurate representations of ships and boats.

Claude Monet was born in 1840 when Boudin was 16 years old. Monet was born in Paris, but his family moved to Le Havre in Normandy when he was five. Monet discovered an early love of drawing and the outdoors. During his school years, he filled notebooks with sketches, especially caricatures of his teachers and fellow students. Even at a young age, Monet became well known in Le Havre.

In 1858, 18-year-old Monet met Eugène Boudin, who was then 34 years old. Boudin recognized Monet’s talent and encouraged him to begin painting landscapes. Monet was a good student and spent a lot of time painting with Boudin on the coast and in the countryside. The similar style of Monet’s early landscape paintings reflects the influence of Boudin.

At the time, Monet was doing caricatures in Paris to earn his living, but Boudin thought that he was wasting his talent. Boudin told Monet, “Come on, Claude—your caricatures are fun, but it’s not real art, I mean art; I mean painting, Claude, painting!”

Boudin was able to persuade Monet to come to Honfleur, near where Monet had grown up, in order to “see the light.” After painting outdoors with Boudin, using portable easels and the recently invented tubed paint, Monet suddenly understood. He later said that it was just like a curtain had been opened in front of his eyes. Monet understood what life and art was all about, and he had his life’s calling.

The two friends spent many hours outside together painting seascapes and the port at Le Havre. The most outstanding feature in Boudin’s paintings is his skies which he frequently made the focus of his paintings. Of course, his ocean waters and the accuracy of the details in the boats and ships in his paintings are also strengths. Seeing the skies in one of Boudin’s paintings in person is breathtaking. It is impossible for the camera to properly capture the nuances of his skies.

Boudin’s style of painting did not change much during his career although his artistry did. His reputation and finances grew steadily, enabling him to begin traveling over Europe, living very comfortably. Finally, in 1892, he was made a knight of the Légion d’honneur in recognition of his accomplishments.

While Boudin had the support and encouragement of his parents, Monet was not so fortunate. Monet’s mother, Louise, was supportive of his art, but his father, Adolphe, was not. Adolphe was in the shipping business and wanted Claude to follow in his footsteps. Adolphe was very harsh, and even though he had the means, refused to help Monet financially. The stern father even refused to pay a 2500-franc exemption fee to prevent his son from being conscripted into the military. When Monet’s mother died in 1857, the bereaved son took her death very hard. Now a widower, Adolphe completely cut Monet off financially.

In addition to his financial difficulties, the conservative ideas of the French art establishment also made it very difficult for Monet and other new artists with new ideas to be exhibited. Everything finally came to a head in 1868 when Monet attempted to drown himself in the Seine River. Monet suffered from bouts of severe depression throughout the rest of his life. Not long afterward, Louis-Joachim Gaudibert became the first of several patrons to support Monet, enabling the artist to provide for his family and to continue his work.

With the stability provided by this patronage, Monet was able to concentrate on his painting and by the 1880s and 1890s finally achieved critical and financial success. Despite this, he still suffered from depression and self-doubt, destroying upwards of 500 of his paintings. Later in his life, Monet wrote to a friend, “Age and chagrin have worn me out. My life has been nothing but a failure, and all that’s left for me to do is to destroy my paintings before I disappear.” We are grateful that he didn’t follow through with the destruction of his paintings.

In 1912, after the death of his second wife, Monet developed cataracts which began to affect his paintings. As the cataracts progressed, he continued to paint what he could see, and his paintings began to appear more abstract with a decided color shift. In January 1923, Monet had surgery on his right eye, but refused the surgery on his left. The changes in his vision can be observed in his series of paintings of water lilies.

Boudin’s influence can be seen in all of Monet’s work, but especially in Monet’s early paintings done during his studies with Boudin. The C. Monet Gallery says, “Perhaps what Monet really took away from Boudin though (besides the en plein air painting), was the method by which Boudin blended the sky and often focused on it, making the sky the point of interest in many of his paintings.”

Two examples of the similarities in their work can be seen (shown above) in The Meuse at Dordrecht by Boudin in 1882 and Monet’s The Regatta at Sainte-Adresse 1867.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Eugène Boudin for showing Claude Monet the light.

For further reading:

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128174560

https://www.eugeneboudin.org/biography.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Monet

https://www.cmonetgallery.com/boudin.aspx

https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-boudin/the-meuse-at-dordrecht-1882