By Holly Henson

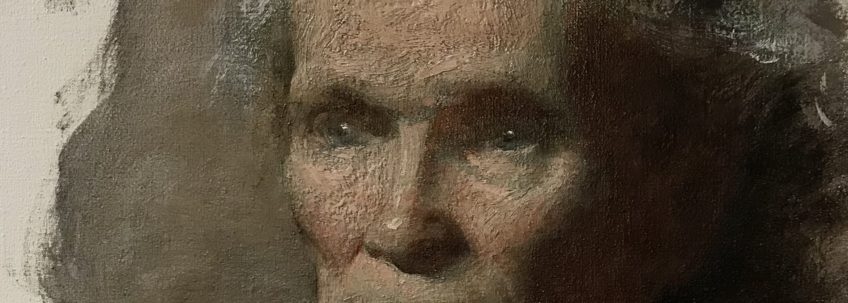

In September, I traveled to Nashville, Tennessee for a three-day workshop with Richard Greathouse. Though a native of Nashville, he currently resides in Florence, Italy, where he is Director of Anatomy and Principal Instructor of the second year painting program at the Florence Academy of Art. While in town, I had an opportunity to view many of Richard’s portrait and figurative paintings at Haynes Galleries, and was moved by their ethereal beauty and tenderness.

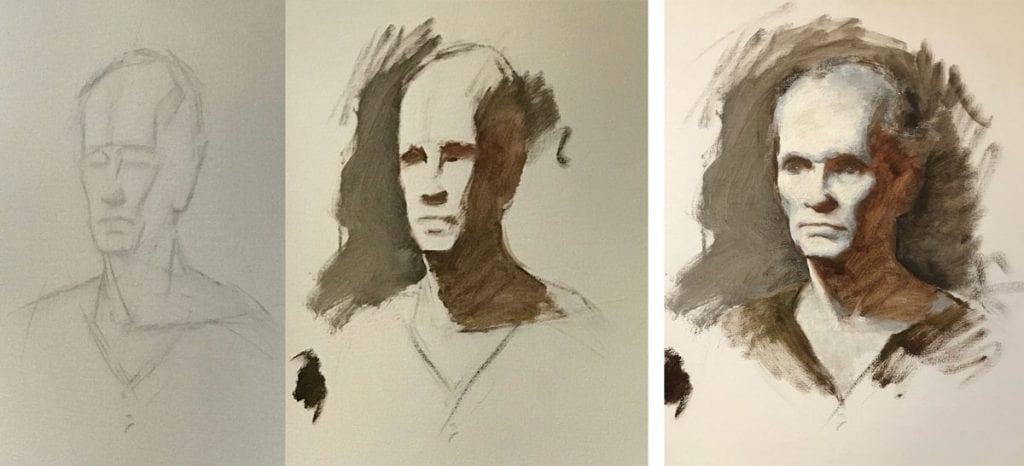

On the first day, Greathouse described his overall philosophy on indirect painting and then began to explain his process with a demonstration. Each subsequent morning, he would demo one step of the process, and then we would practice this step while working from one of two life models.

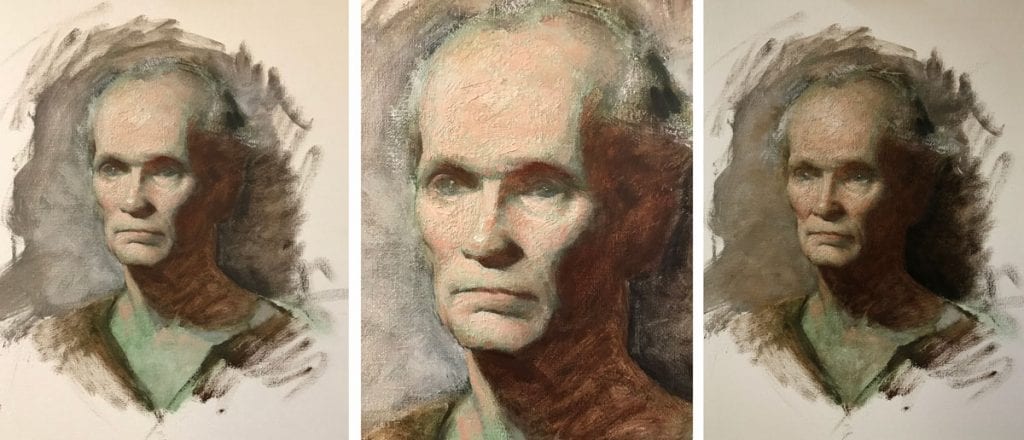

Instruction on day one was focused on creating a solid structural foundation with a simple but accurate drawing and underpainting. Drawing the model using soft vine charcoal, he emphasized the importance of structure and anatomy. He then brushed off the excess charcoal with a soft fan brush, leaving just a ghost drawing. Using a mixture of cobalt blue and burnt umber, he began with the darks, first in the shadows and then the background. His medium was a thin mixture of one tablespoon gamsol to ½ teaspoon pale linseed oil (Chelsea Classical Studio’s brand). This is fast drying and can be pushed warmer or cooler as needed. In this demo, he painted the form and cast shadows warm, and added more cobalt to his mixture for a cool darker background. To prevent the shadows from getting too dark at this early stage, he wiped off some of the dark paint. Next, he moved to the lights, using pure white for the entire mass of light areas. He painted thickly, using varied, casual brushstrokes, intentionally building an interesting surface landscape while keeping the lights highly keyed because he knows the painting will darken in future stages. He uses both lead white and ceruse white, which is made by Natural Pigments/Rublev and combines lead white and calcite in one mixture. The addition of calcite makes ceruse more transparent than a regular lead white. Only between the edges of light and shadow did he add a little bit of cobalt to the white for turning the form.

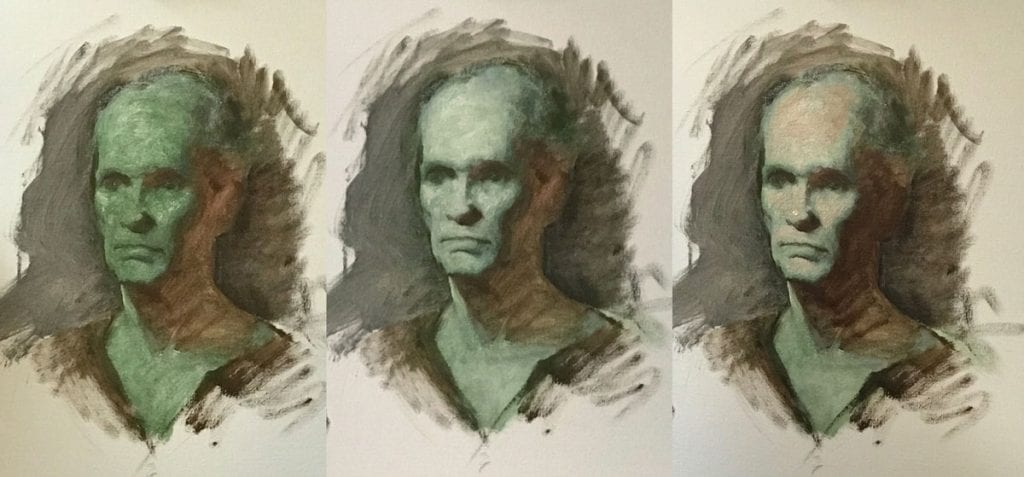

The second day we built upon the underpainting with a step called dead coloring. Normally, one would have to wait for the underpainting to dry, but to speed it up for our limited amount of time, we added cobalt drier, which is typically not a recommended studio practice. This is an awkward stage, where one really must trust the process. Greathouse describes it as a game of chess, in which one move is played specifically to set up for what’s to come. He first mixed a warm shade of green using chromium oxide, viridian, and a little bit of earth red, such as venetian red. He combined this with a somewhat fatter medium of one part gamsol to one part pale linseed oil. Richard brushed the green mixture into all the light areas of the painting and then wiped it off, leaving a green couche to paint into. Couche is a French term describing a layer of color applied thinly that is meant to be painted into while still wet. Starting with a cool/green couche prevents the painting from getting too warm later as glazes are applied. Furthermore, the coolness will continue to show the broken brushstrokes creating an appearance of life and blood under the skin. We painted into the couche with correct flesh mixtures, applied in a semi-opaque method using broken brushstrokes and thick impastos in the lightest areas. Overall, we kept the painting keyed high, knowing that it would darken further in the next stage with glazing.

The last day, we finished with glazing and houding. Glazing was achieved using pure linseed oil and a warm neutral mixture of red and green pigments. The two main combinations Richard uses are chromium oxide green + vermillion or cadmium scarlet, and viridian + Indian or venetian red. He does not use much yellow in his paintings, only a touch of yellow ochre or genuine Naples yellow. We painted the warm glaze into the lights and shadows, but wiped much of it away in the light areas to leave a thin layer of transparency.

Finally, he described and demonstrated a painting concept from the Dutch Golden Age—houding—which is the process of integrating the whole painting together. He asked us to imagine the painting as a window into a world, an object in and of itself, not just a representation of reality. In a way the painting becomes autonomous, and the artist becomes the vessel. At this final stage, we focused on making sure we had a variety of soft and hard edges, sharpening and hardening as necessary to connect and distinguish forms. If necessary, we re-keyed the lightest lights and applied selective glazes. Sometimes Richard uses glazes to vignette the painting in this final stage. The most important thing here is to move beyond just documenting what you actually see, and to think compositionally and holistically.

If you ever have the opportunity, I highly recommend studying with Richard Greathouse. His body of work and his philosophy is inspiring, plus he’s a wonderful teacher. Although I already used some indirect painting techniques in my work, this introduced me to many new possibilities, techniques, and ways of thinking about indirect painting. I came home with many new tools, inspired to try some of these techniques in my own work.

To see more work from Richard Greathouse, click here for his instagram.