By Luana Luconi Winner

Artemisia Gentileschi was born on July 8, 1593, into the male-dominated world of 16th century Rome, where the Italian culture was built on the premise that a woman was either a wife, mother, nurturer, mistress, or servant. At age 12, Artemisia became the caregiver for her four younger siblings after their mother died. At a time when women had no opportunity to advance academically or artistically, one young girl insisted on developing her God-given artistic talent. The National Gallery in London said, “Artemisia Gentileschi turned her suffering into some of the most dramatic paintings of the Italian Baroque, casting herself in the leading role.”

Being the only child of the family with an aptitude and an interest in art, her father, Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi, permitted her to work in his workshop/studio to learn the basics. This would have been the only way in which a young girl could have studied art. During her formative years—from the age of seven to thirteen—she was greatly influenced by Carravagio, a close friend of her father’s and a frequent visitor to the studio who came to borrow props and share stories. When Carravagio permanently left Rome after committing a murder in 1606, Artemisia continued to study his work, including the altar pieces in Santa Maria del Popolo where her mother was buried.

Recognizing that his own lack of skills as an instructor might be limiting Artemisia’s development, her father hired artist and teacher Agostino Tassi to continue teaching her. Born in Perugia, the son of a furrier, Tassi had changed his family name from Buonamici and claimed to be of Roman nobility, the adopted son of Marchese Tassi. Now he is best known for being Artemisia’s rapist.

By age 15, in the early 17th century when women were not considered important, Artemisia was producing professional quality work. Her painting Susanna and the Elders dates from 1610, when she was only 17 years old. Her 67” x 48” interpretation of the Old Testament story incorporated a triangular design of two large, clothed, whispering, threatening male figures intimidating the bathing nude woman in a lascivious and oppressive manner.

Brilliantly executed, the art world first believed that surely she had been helped by her father. But it has been noted that the experience and complex expression found in the painting is perhaps there only because the story was told by a woman, in a manner only a woman could understand.

Within a year of this work, she became yet another victim of her teacher, the previously accused Tassi, who brutally raped her. But unlike the typical handling of cases such as this, Artemisia took him to court. The Roman justice system of the time tortured the victims in court to ensure the accusations were truthful. Artemesia never wavered. Her attacker was eventually sentenced to a five-year exile from Rome, but because of his high-ranking connections, the sentence was not enforced. Tassi’s crime shaped Artemisia’s future as a “feminist” before the word had ever been coined.

Her determination and skill bolstered her resolve. In letters to a Sicilian patron she wrote, “I will show Your Illustrious Lordship, what a woman can do. You will find the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman.”

Artemisia was off to Naples, then north to Florence, Venice, and, eventually, London. After marrying Pierantonio Stiattesi, they went to Florence where she sought out the Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici as a patron. She continued to make acquaintances with influential art patrons, including Cassiano dal Pozzo and the astronomer Galileo Galilei.

In 1615-1616, at age 23, Artemisia became the first female member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence. Between 1613 to 1618—the period during which this honor was bestowed—it is interesting to note that she also bore five children. Only one daughter survived to reach adulthood.

Her paintings were powerfully autobiographical. In her two paintings of Judith Beheading Holofernes (one hangs in the Uffizi in Florence and one in Capodimonte in Naples), she clearly painted herself as Judith inflicting the final sword stroke to Tassi’s neck. In this representation, she is pouring out her innermost feelings as someone brutally damaged in body and spirit.

Though her women were taken from biblical tales or mythological stories, as was much of the work of the day, she succeeded as a painter by depicting statements of empowerment at a time when women had no rights. By 1638, her international clientele included Charles I, who personally invited her to London to create work for the British court.

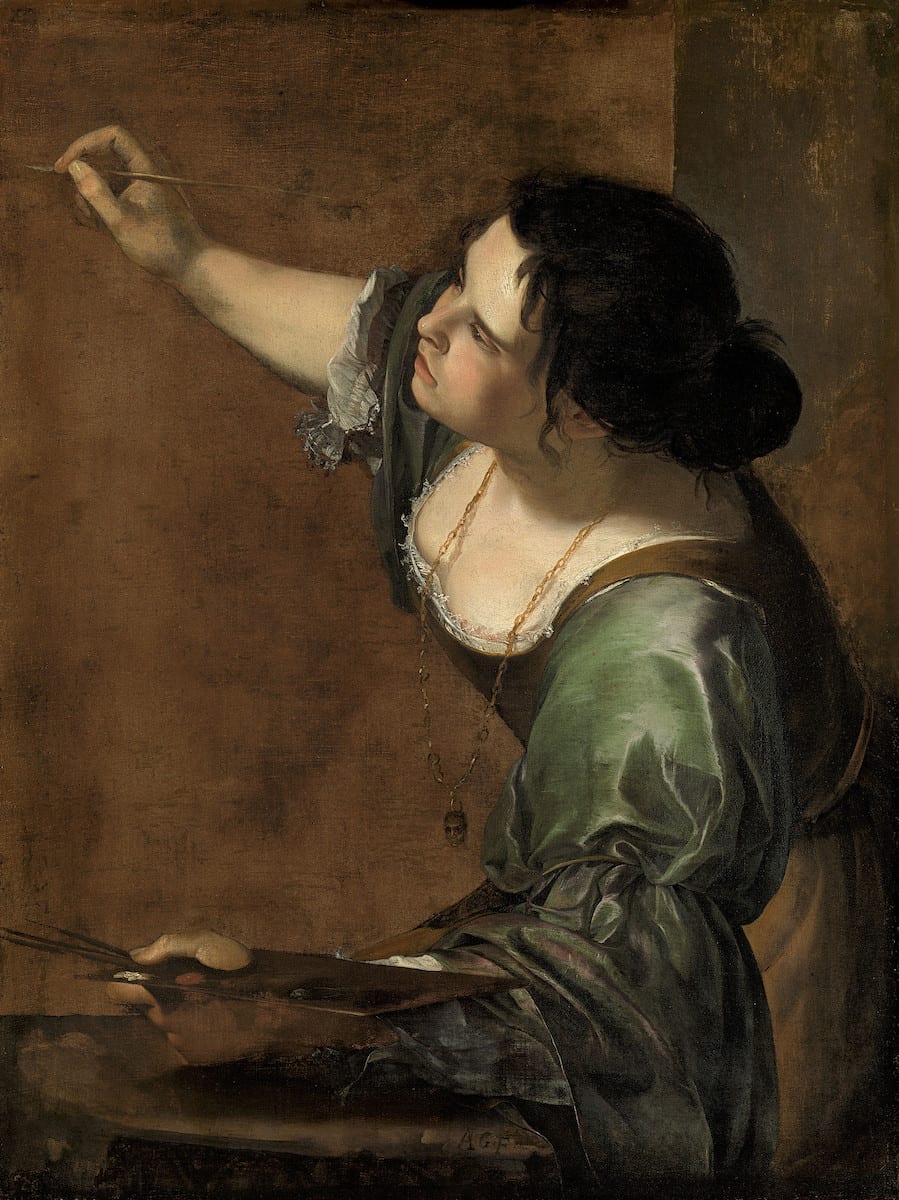

While in London, she painted what some consider her most important work. Armed with a brush instead of a sword, in Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting she represents herself as a physically strong and dynamic person.

Of approximately 60 paintings remaining today, 40 are dominated from the viewpoint of the female figure. Artemisia took the lowly maids, the unnoticed servants, and the victims, often painted by the men of the day, and turned them into brilliant trailblazers, strong subjects, and survivors.

Artemisia at the National Gallery, London December 3, 2020 to January 24, 2021 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/artemisia

Luana Luconi Winner, portrait artist, author, and instructor, is a Juried Member of the Portrait Society of Atlanta; a founding member and NC Ambassador of the Portrait Society of America; a Master Circle Member of the International Association of Pastel Societies; a Signature Member of the Pastel Society of America, Pastel Society of North Carolina, Southeastern Pastel Society, and others. Author of F+W Publications/ Penguin Random House “Painting Classic Portraits: Great Faces Step by Step” ISBN-10: 1440321108; ISBN-13: 978-1440321108