By Holly Henson

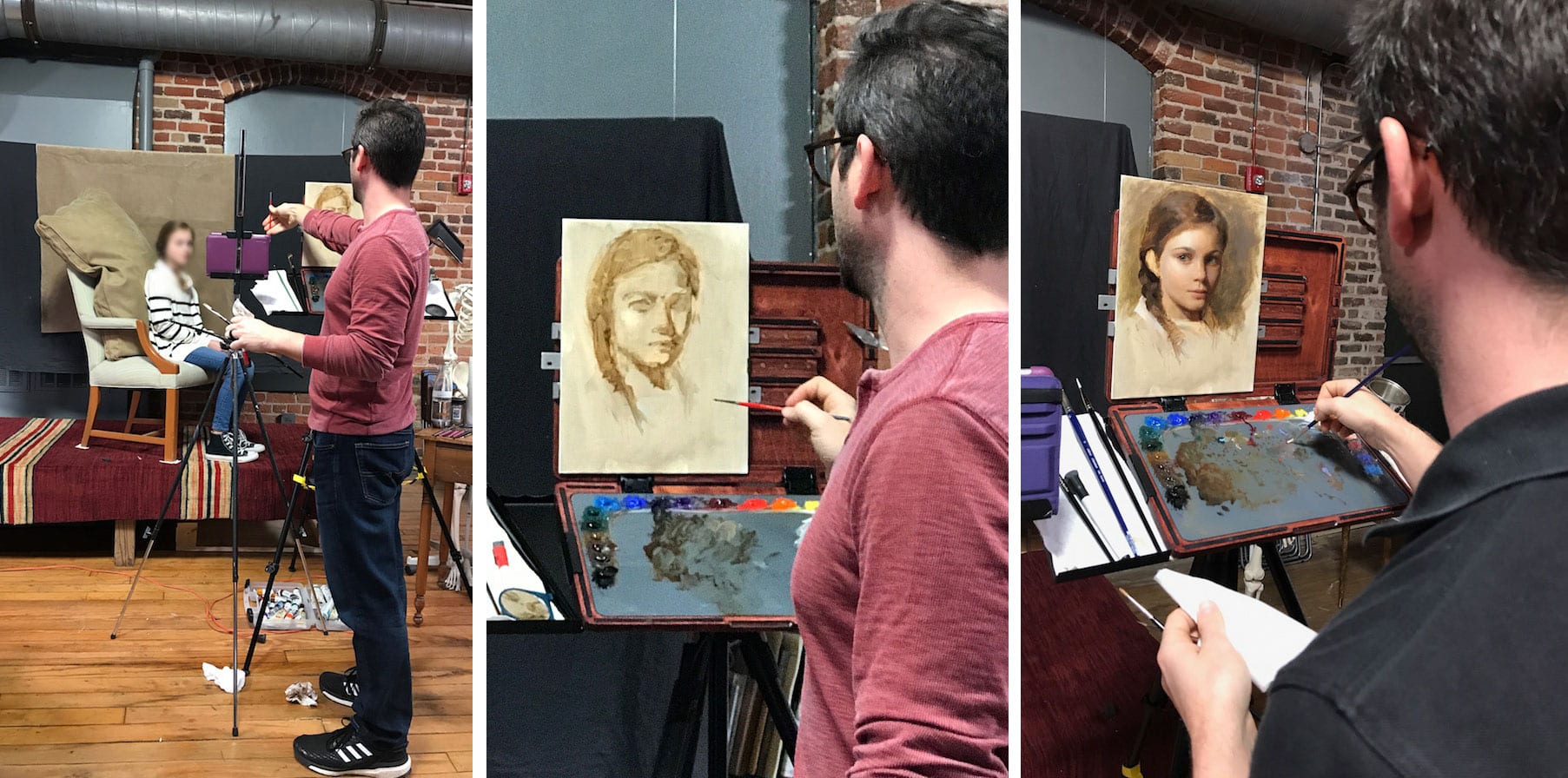

Recently, I attended a workshop on Children’s Portraiture offered by the artist, Louis Carr. It was a wonderful experience and I recommend taking a workshop with him if ever given the opportunity. Not only is he talented and skilled, but also truly inspiring and generous with his knowledge.

Throughout the workshop, we had two adorable children posing, one young girl in the morning for Carr’s demo, and her younger sister in the afternoon for the workshop attendees. An unexpected perk was learning how Carr keeps children in position and engaged while he paints. He attaches an iPad, on which he plays movies, to a stand in front of the model, thus mitigating potential boredom issues. This keeps the children focused, in the same position, and looking towards the same spot. He selects a movie that will evoke some emotion, and has a camera ready to spontaneously capture any changing expressions. When doing small color studies for portrait commissions, he’s found this to be a useful tool. The color studies, along with his photos, become reference material for fully developed paintings in the studio.

Each day, we focused on one aspect of the painted portrait: drawing, value, and finally color. Addressed in depth was how easy it is to unintentionally age a child. Many tips on how to capture the essence and youth of a child were specifically related to the drawing process. Suggestions for avoiding some pitfalls that age children included:

- Minimize any bags under the eyes. Even if observed on the subject, they can almost be excluded altogether.

- Large eyes convey youth, so don’t make the eyes too small. To emphasize a youthful innocence, you may even get away with making the eyes slightly larger than reality.

- Downplay the bridge of the nose. A relative flatness to the nose distinguishes a child’s face from that of an adult. It is easy to subconsciously give this area more dimensionality than it really has, and that ages a child.

Over the course of the three days, Carr also shared his process for capturing a likeness—no matter the subject’s age. As he focused on drawing, he advised that he begins by capturing the gesture of the pose—not yet worrying about precise measurements, because he knows that corrections will inevitably follow. Concurrently, he observes and notes the shadow shapes. Only after the gesture is established does he correct and fine-tune the drawing: first with comparative measurements, then with angles and tilts. He does not rush this process, but works carefully to delineate the defining triangle of eyes, nose, and mouth before moving forward.

The second day was devoted to developing the three-dimensional form using values. Carr uses a neutral value string to turn the form, beginning with a carefully observed hierarchy of values across the forehead. He moves on to the rest of the face, establishing plane changes while keeping the value hierarchy intact, and pays close attention to shadow shapes, distinguishing between form and cast shadows.

The final day was an immersion into color, which Carr approaches with care and grace. Although he uses a full-color palette, including some high-chroma pigments, his color mixtures appear subtle and elegant. He advises that most true skin tones are low-chroma, and too many high-chroma mixtures at this stage could overwhelm and compete with each other, the result of which is that no color feels truly important. He practices the concept of hierarchy of importance at this stage. In his work, he ensures that something in the portrait plays a lead role, and other elements of the portrait play supporting roles.

One of the many things I loved about this workshop is how Louis Carr shared so completely his working process—so that we could return to our own studios and not only practice, but practice with intention. Inspired, I returned home with many more tools to employ in my own portrait painting process.

For more information on Louis Carrr, visit East Oak Studios.